Digital Memorials and the Online Archive of Grief

The Early Internet - Virtual Memorials

Content warning - this blog post mentions suicide, grief and death

The Internet entered the public domain on 30th April, 1993. Later that same year The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier by the cultural critic and pioneer observer of virtual communities Howard Rheingold (1993) was published, which detailed his experiences in the mid- to late-1980s on The WELL, a virtual community established in 1985 that still operates today. In his chapter The Heart of the Well, he discusses the death of a fellow WELL user named Blair Newman who took his own life. Not long before Blair ended his life, he removed everything he had ever contributed to the site, an act then known as ‘mass-scribbling.’ (p.34) In the aftermath of his death, the family requested virtual eulogies be posted on WELL for them to collect, and the real-life funeral was followed by a virtual one. (p.36-37)

Two things are evident from Rheingold’s experience: one is that people have been using online spaces for grieving practices even before there was a publicly available Internet. The other is that a person’s existence online, and indeed the memory thereof, can be far more precarious than most Internet users are inclined to believe until presented with mortality. With that said, even if a person has never had any particular proclivity to engage in online socialisation, their memorialisation can still be pursued by friends and loved ones online as well as in physical memorial. As Socolovsky (2004) indicates, “For those who have placed a memorial online and return to read it and dwell with it, cyberspace, as a resting “place” for the departed, serves as a point of contact between the world we know and the afterlife.” (p.474)

Not long after Rheingold’s book was published, Human Development professor Pamela Roberts (2004) was conducting research into the creation of web memorials. She noted that as an emerging trend, there were few “common cultural rules” (p.41) in the 1990s to dictate how a web memorial should be composed. In terms of folklore and folk practice, this pertains to what folklorist Simon J. Bronner (2009) refers to in his description of the Internet as “the transgressive folk web…a separate location or space in which traditions arise and are constituted.” (p.22)

The three oldest memorial sites are those that were created in 1995: The World Wide Cemetery (2025) The Virtual Memorial Garden (2025) and Dearly Departed (2025) (Roberts, 2004 p.42). These three web domains are still occupied thirty years later, although only World Wide Cemetery and the Virtual Memorial Garden still operate in their original capacity.

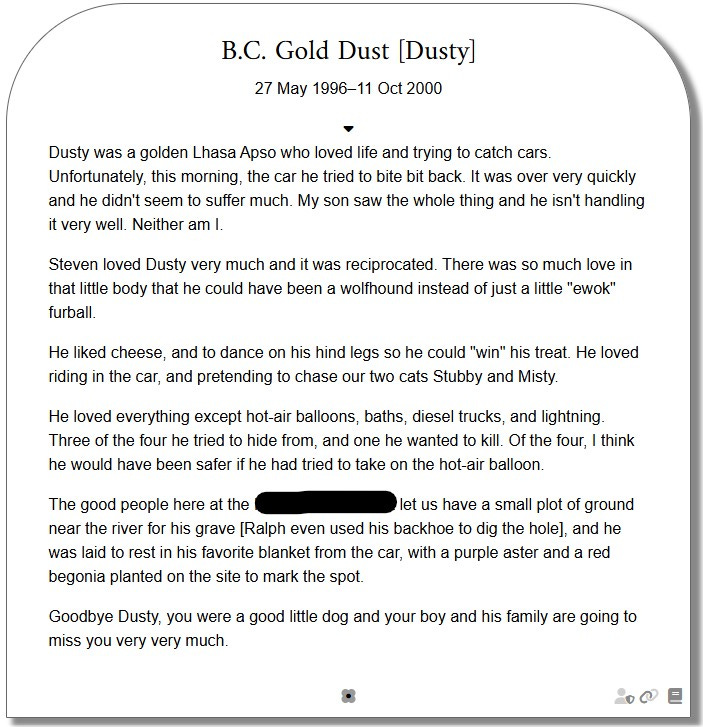

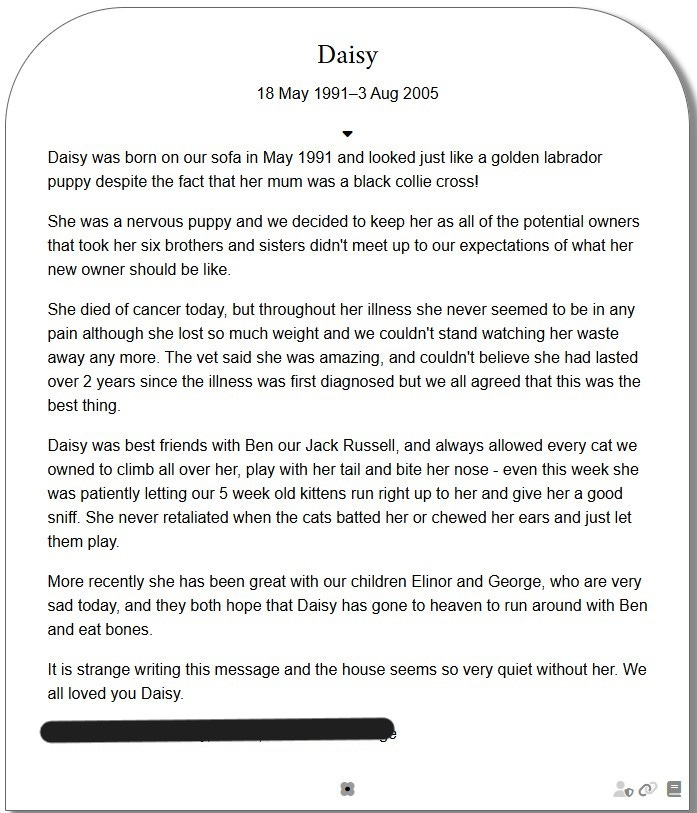

The Virtual Memorial Garden was created by Lindsey F. Marshall, Emeritus Professor of Educational Practice in Computing at Newcastle University, and claims to be the first and oldest virtual memorial. Memorials are listed alphabetically and offered for both humans and pets, with the messages posted in a graphic resembling a tombstone. There is also a visitors’ book. The limited interface characterises bears similarity to a physical burial ground, except that people can write as little or as much as they want on the ‘tombstones’.

The World Wide Cemetery, which also claims to be the oldest virtual memorial, offers a ‘Visitors and Flowers’ section for each memorial where loved ones can post pictures and messages when visiting the virtual memorial. The cemetery can be browsed by country, and it is clear from the memorials in the USA that people have been using this site to memorialise as recently as 2022, with visitor posts and pictures uploaded as recently as 2024. The virtual rituals that started with these sites still draws people to use them in an era dominated by more modern technology, similarly to how people still desire their resting place to be a church cemetery rather than more contemporary forms of internment.

Another site, Virtual Memorials (1996), is also still operating and people are still uploading memorials to the site as of March 2025, indicating that they still have a desire to use this form of virtual memorial while, and perhaps because, it remains operational. The site’s Message Board forum, where people can post new messages dedicated to a previously uploaded memorial, also indicates this. One of the most recent posts shows gratitude to the Virtual Memorial for remaining accessible even in the 2020s:

Another poster has sporadically commemorated her brother’s birth and death date via the forums since 2007 up until 2022, and would speak to her deceased brother in the first person:

The continued use of these virtual memorials shows how important they remain to the mourners, who consider these virtual shrines just as necessary to their grieving process as visiting a physical resting place, or having a conversation with the dead in that physical space.

The web page for Dearly Departed now functions as an online shop for remembrance memorabilia, but its original function has been ‘captured’ on The Wayback Machine (2025), where users have screenshotted the site’s layout to preserve it in the Internet Archive. While still able to browse the site through the WM, pages include an alphabetical ‘Mausoleum’ directory and a perpetual calendar (albeit no longer functioning), which aimed to help people track significant dates.

This virtual memorial’s existence only within the Internet Archive lends itself to a metanarrative of the Internet - where a shrine to the dead is now itself a shrine to an older form of virtual grieving. Drawing on Socolovsky’s idea of a cyber-resting place connecting our world with the afterlife, this website’s afterlife provides a further extension of a liminal space for the dead, where the website has ‘died’, but ghostly imprints remain as a final connection to the people enshrined there, to the website itself, and to an era of the Internet which is now in the past.

While these sites are now virtual relics in terms of their layout design, the desire to keep using them has endured while the platforms remain available. The loss of sites such as Dearly Departed highlights an issue with the preservation of digital mourning practices, as shall be explored in the second blog post.

Bibliography

Bronner. S. J. ( 2009) Digitizing and Virtualizing Folklore. In: T. J. Blank, ed. Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, pp. 21 - 66.

Rheingold. H. (1993) The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Reading: Massachusetts. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Roberts. P. (2004) Here Today and Cyberspace Tomorrow: Memorials and Bereavement Support on the Web. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 28(2), pp. 41-46.

Socolovsky. M. (2004) Cyber-Spaces of Grief: Online Memorials and the Columbine High School Shootings. JAC, 24(2), pp. 467-489.

The Virtual Memorial Garden (2025) [Online] Available at: https://catless.ncl.ac.uk/vmg/ [Accessed 8 April 2025].

The Wayback Machine (2025) [Online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20000520093642/http://www.dearlydeparted.net/ [Accessed 9 April 2025]

The World Wide Cemetery (2025) [Online] Available at https://cemetery.org/ [Accessed 8 April 2025].

Web 2.0 - Makeshift Memorials and Lost Archive

Content warning - this blog post mentions suicide and death

In spite of the longevity of earlier virtual memorials, those which remain active and the research conducted on them in the 1990s are a vital resource of grieving rituals from the early Internet. Even in the early years of the twenty-first century, Socolovsky (2004) noted that the domain for condolences.com had been put up for sale, and that “No ghosts of the past emanate from the remains of this memorial website. Instead, it can only be a comment on events of the recent past…and the request to buy the domain emphasizes the fragility of real estate on the internet.” (p.474) Unlike Dearly Departed, there are no Wayback Machine captures of the original memorial site, and thus all messages of love, commemoration and loss are lost. This is something that has come to affect some of the new social media platforms that became popular after the turn of the millennium.

While some early virtual memorials still operate, and are still used by those who originally posted to them, in the 2000s the rise of social media began to overshadow the creation and use of web pages by individual Internet users. This phase of Internet use has become known as Web 2.0, a loose term for the World Wide Web that emerged in the twenty-first century where platforms and applications focused on participatory social usage of the Internet in the sharing of information, resources and interconnectivity (McHaney & Sachs 2016, p.11). The early pioneering social media sites of this era include MySpace, Flickr and YouTube, but it was also marked by the increased usage of blogs and wikis such as Wikipedia. (Murugesan 2007, p.34 -36)

Roberts’s (2004) idea in my previous blog post of the early Internet representing freedom from a pre-established cultural etiquette persisted in how people express grief online from the 1990s into the Web 2.0 era. This can be seen in the examples of how MySpace became a new frontier in spontaneous memorials for the dead, on profiles of people, particularly young people and adolescents, who had died unexpectedly. MySpace was one of the most popular social media platforms among young people in the mid- to late-2000s, with a Pew Research Center survey finding that 85% of teenage respondents in 2007 used MySpace compared to 7% having a Facebook profile. (Lenhart and Madden, 2007) Furthermore, the growth in social media users over such a short phase of the 2000s was remarkable, rising from 8% in February 2005 to 35% by December 2008. (Lenhart, 2009) Like Rheingold and WELL in the 1980s, these people were part of a new frontier, and the etiquette and rituals they were creating were unprecedented.

In 2007, an article from The Detroit News detailed how the suicide of record producer David “Disco D” Shayman had prompted his fans and loved ones to post tributes on his MySpace profile. The article’s author wrote that these were “examples of people using the Internet in a new way: As a mourning place.” (Graham, 2007) An article from Wired that same year mentions MySpace users creating a “makeshift memorial” (Wallace, 2007) for a friend who had been killed by a tiger. NBC News ran a piece about MySpace mourners, citing an example of people posting on a friend’s profile within hours of the news of their death (Heher, 2007). The viral nature of this type of mourning indicates a new spontaneity that distinguished the phenomenon from the organised ritual of earlier virtual memorials.

While my previous blog post has demonstrated that the Internet has always been a place of mourning, Graham’s description of the MySpace mourners’ “Uncensored, stream-of-consciousness comments” (2007) speaks to how social media was never officially intended for mourning but profiles instead became spontaneous places to mourn, grieve and tell stories. This is what Falconer et. al (2011) see in Internet grieving as “changes in attitudes towards privacy and…an increased acceptance of more public expressions of individual opinions and emotions.” (p.82)

The transition from the Internet of the 2000s and 2010s to the current era has seen yet more losses to the archive of virtual memorials, in a way that has proved more permanent. Since a major fault in MySpace’s server migration every post, video, photo or song shared before 2016 now no longer exists (Hern, 2019). It is through news coverage that proof of these practices’ existence exists, and even then embedded links in the articles are now broken. An entire resource of contemporary grief rituals, lost forever.

While the archive of these makeshift memorials is wiped from cyber history, the practices that formed in these new social media sites have endured in other Web 2.0 platforms which still operate today, specifically YouTube, which shall be explored in my next blog post.

Bibliography

Falconer, K., Sachsenweger, M., Gibson, K. & Norman, H. (2011) Grieving in the Internet Age. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), pp. 79 - 88. [Online] Available at https://www.psychology.org.nz/journal-archive/Falconer.pdf [Accessed 14 March 2025]

Graham. A. (2007) Myspacers turn deceased users' pages into memorials. The Detroit News [Online]

Available at: https://eu.ocala.com/story/news/2007/02/03/myspacers-turn-deceased-users-pages-into-memorials/31184397007/

[Accessed 7 April 2025].

Heher. A. M. (2007) Mourning teens express grief on MySpace. NBC News [Online] Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna17172743 [Accessed 10 April 2025].

Hern. A. (2019) Myspace loses all content uploaded before 2016. The Guardian [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/mar/18/myspace-loses-all-content-uploaded-before-2016 [Accessed 8 April 2025].

Lenhart. A. & Madden. M. (2007) Social Networking Websites and Teens. Pew Research Center [Online] Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2007/01/07/social-networking-websites-and-teens/ [Accessed 10 April 2025].

Lenhart. A. (2009) Main Findings. Pew Research Center [Online] Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2009/01/14/main-findings-13/

[Accessed 10 April 2025].

McHaney. R. & Sachs. D (2016) Web 2.0 and Social Media: Business in a Connected World. [Online] 3 ed. s.l.:Ventus/BookBoon. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Sachs-3/publication/308128501_Web_20_and_Social_Media_Business_in_a_Connected_World/links/61438939d5f4292c01fe6a62/Web-20-and-Social-Media-Business-in-a-Connected-World.pdf [Accessed 13 March 2025]

Murugesan. (2007) Understanding Web 2.0. IT Professional, 9(4), pp. 34 - 41.

Socolovsky. M. (2004) Cyber-Spaces of Grief: Online Memorials and the Columbine High School Shootings. JAC, 24(2), pp. 467-489.

Wallace. L. (2007) MySpace Memorials Pay Tribute to Tiger's Victim. [Online] Available at: https://www.wired.com/2007/12/myspace-memoria/ [Accessed 10 April 2025].

“Music, When Soft Voices Die” YouTube’s Virtual Memorials

Content warning - this blog post mentions grief and death

When folklorist Robert Dobler (2009) conducted a survey of mourners on MySpace message boards for his essay Ghosts in the Machine: Mourning the MySpace Dead, he questioned the extent to which community played a part in the grieving process of the individuals posting comments, saying that while the comments bore similarity in messaging, he rarely saw posters “acknowledging the sorrow of any other message-poster…giving the impression that MySpace mourners grieve alone, together.” (p.179) He also makes the astute point that such comments entering the online public domain means that they can and will be viewed by anyone at any time. (ibid.) This is especially true with the messages and stories of grief that have, over the course of nearly two decades, been posted to music videos on YouTube.

While MySpace memorials are lost to the ether of permanent deletion, and Facebook having factored memorialised user profiles of the deceased into their policy (Topping, 2009), YouTube has stayed the course as a perennially popular social media platform where there is no governed idea of comment etiquette with regards to grieving and commemoration. As it enters its twentieth year, YouTube remains the most used online platform by US adults (Dannenbaum 2025) and the second most popular platform globally with 2.53 billion users. (DataReportal, 2025)

Its popularity has endured due to the universality of interest encapsulated in its audiovisual content, as well as the facilitation of discussion in its comment sections. The phenomenon of what is callously termed ‘trauma dumping’ (where a person overshares distressing personal information (Harris, 2023)) or the more neutrally termed ‘mini-autobiographies’ in YouTube comments, especially under music videos and songs, has not gone unnoticed by social media users on other platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and Reddit:

While some appear dismissive in their remarks about the outward display of emotion, others show a positive interest, sometimes humorously, in how people use music with associated with memories to share their stories of grief and loss:

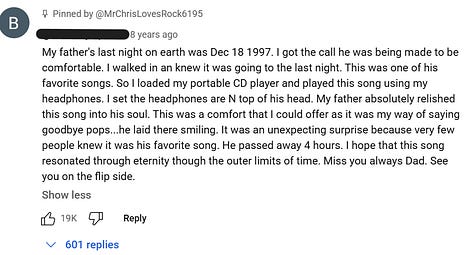

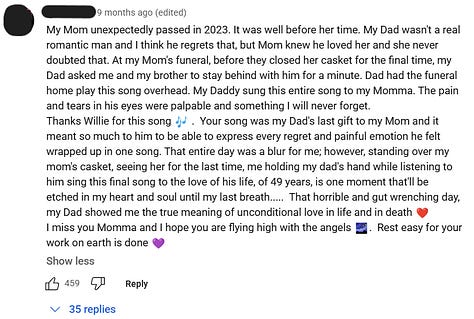

I have conducted fieldwork on several music videos with examples of memorial comments. Through observation there are identifiable patterns that re-emerge between videos. The music they are commenting on is usually popular music from the twentieth century, and will often have an emotional connection to a family member or loved one, with the stories recounting the origin of that connection. As per Dobler’s observations about MySpace, they do not form part of a wider discussion or support group about grief, although people may reply with condolences or similar experiences. They are spontaneous, and influenced by memories associated with the music. They are in this way very similar to the makeshift memorials formed on MySpace in the 2000s.

In some cases, the lyrics have a potent meaning to the listener associated with their lost loved one, such as these under Peter Gabriel’s Solsbury Hill (1977) with the lyrics “Son, he said, grab your things, I’ve come to take you home” (Gabriel, 1977) and with the refrain “Take a load off, Fanny…And you put the load right on me” (Robertson, 1968) in The Weight by The Band (1968):

These show not only how people interpret their own lyrical meaning in popular music associated with powerful memories and emotions, but also that the free access to these songs along with an open comment section provides a platform for memorialising that is separate from traditional forms of mourning.

There are also several touching tributes to pets, such as in the comments of Kate Bush’s And Dream of Sheep (1985) Golden Brown by The Stranglers (1982) and The Weight by The Band:

As is evident in these pet comments people will, as the X posts imply, often post longer form stories with an autobiographical element explaining the connection to a deceased loved one and the song. These comments from Willie Nelson’s cover version of Always On My Mind (1982), Brothers in Arms (1985) by Dire Straits, and another from The Weight by The Band also demonstrate that:

What is remarkable about the tone and content of these comments is how much they bear a similarity to the memorials and comments posted on the virtual memorials of the early Internet. As referenced in my first blog post, the Virtual Memorial Garden offers memorials for pets, where people felt able to write longer form memories:

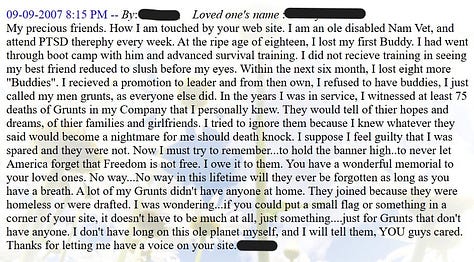

The long-form autobiography style of commenting is also present in the forum pages on Virtual Memorials:

This indicates that while the platforms have changed, the way that grief is expressed in online memorials is still driven by the freedom of expression granted by Internet culture. As Hillis (2018) describes it, “the familiarity of the online setting lends itself to a comfortability that encourages the virtual dissemination of deeply personal information.” (p.11) This comfortability is innate in virtual living, and to acknowledge this is to acknowledge that while the platforms through which we interact may change, or even permanently disappear, there is a method of online comportment which drives ritual behaviour such as memorial and remembrance. The immeasurable expanse of the Internet is such that older traditions such as virtual memorials may go unnoticed by the majority, but people will always feel compelled to share their stories of love and loss in whichever space feels pertinent to them, as became apparent during the beginning of Web 2.0 and has endured with a long running platform like YouTube.

The idea for this assignment was influenced by my own loss, that of my father, and the connections I drew from comments in the videos of his favourite music. His Facebook page still exists, where family and friends still wish him a happy birthday every year. I still write messages to him on WhatsApp every now and then. The dedication to honouring him through his virtual presence keeps his memory alive as much as in-person storytelling does. Though some Internet virtual memorials have been lost, those that still remain tell a touching story of how people have coped with their grief in the online world, and are an important source of contemporary ritual that, as long as the pages remain active, can be preserved in our wider social history.

Bibliography

Bush. K. (1985) And Dream of Sheep, The Hounds of Love [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8UUVcGskEw&ab_channel=KateBush-Topic [Accessed 7 April 2025

Carson. W., Christopher. J. and James. M. (1972) Always on My Mind, Always On My Mind (Willie Nelson) [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7f189Z0v0Y&ab_channel=WillieNelsonVEVO [Accessed 7 April 2025]

Cornwell. H., Burnel. J-J., Greenfield. D., Black. J. (1982) Golden Brown, La Folie [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-GUjA67mdc&ab_channel=benskitv [Accessed 9 March 2025]

Dannenbaum. C. (2025) 5 facts about Americans and YouTube, The Pew Research Center [Online] Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/02/28/5-facts-about-americans-and-youtube/ [Accessed 11 April 2024]

DataReportal (2025) Global Media Statistics [Online] Available at: https://datareportal.com/social-media-users [Accessed 6 March 2025]

Gabriel. P. (1977) Solsbury Hill, Peter Gabriel (Car) [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OO2PuGz-H8&ab_channel=PeterGabriel [Accessed 7 April 2025]

Dobler. R. (2009) Ghosts in the Machine: Mourning the MySpace Dead. In: T. J. Blank, ed. Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan: Utah State University Press, pp. 175 - 193.

Harris. M. (2023) Should I Censor Myself in Therapy? Psychology Today [Online] Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/letters-from-your-therapist/202206/should-i-censor-myself-in-therapy#:~:text=Trauma%20dumping%20is%20unloading%20one%27s,and%20may%20hinder%20therapy%20progress [Accessed 11 April 2025]

Hillis. J. (2018) Digitalizing Death: A Study of the Influence of Social Media on the Grieving Process. Senior Honors Thesis. Boston College. Available at: https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:108016/datastream/PDF/view [Accessed 11 March 2025].

Knopfler. M. (1985) Brothers in Arms, Brothers in Arms [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhdFe3evXpk&ab_channel=DireStraitsVEVO [Accessed 7 April 2025]

Robertson. R. (1968) The Weight, Music From Big Pink [Online] Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFqb1I-hiHE&ab_channel=ChrisAwad [Accessed 11 February 2025]