Tolpuddle: A Case Study in Political Folklore

The Origins of a Movement - Symbolic Landscape and Ritualised Politics

When imagining the origins of the trade union movement, most people probably wouldn’t look to a small, picturesque Dorset village. Blake’s ‘mind-forg’d manacles’ seem far removed from the Piddle Valley. Yet with the brutal sentencing in 1834 of six agricultural workers to hard labour in Australia and Tasmania, the men who would be immortalised in history as the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the national image of the village of Tolpuddle was fundamentally altered. George Loveless, James Loveless, James Brine, Thomas Standfield, John Standfield and James Hammett were all sentenced under the Mutiny Act of 1797 for swearing a purportedly illegal oath of solidarity and establishing a Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers. Eventually obtaining a royal pardon and release, the six men became some of the most recognised figures in trade union history.

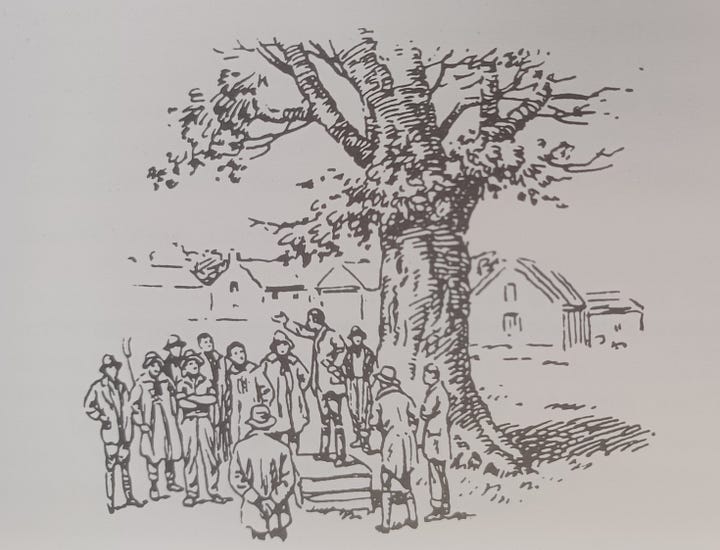

What happened to the Tolpuddle Martyrs is set down in historical fact, but their story has “entered the pages of trade union folklore”. (Empson 2018) This is exemplified by the popular tale of how the six, led by George Loveless, would gather to discuss their political plans under a sycamore tree on the village green. The tree has come to be known as the Martyrs’ Tree, and it still stands to this day. The tree’s significance to the foundation of the trade union movement has been frequently recounted as part of their story. Nevertheless, there is no documented account of the oath being sworn beneath the tree (Western Daily Press, 1969). Norman (2008) frames it as ‘tradition’ that the Martyrs would regularly meet to discuss their ideas under the tree, but since the court testimonies against the six by Edward Legg and John Lock in 1834 detail that the actual swearing of an oath took place at Thomas Standfield’s house, the tree’s involvement in the Martyrs’ story has become embedded as a popular legend.

The attribution of open space in the landscape, particularly trees, to rural political dissent has precedence in England. A prime example is Kett’s Rebellion, which took place in 1549 nearly four hundred years before the events in Tolpuddle. Robert Kett, a landowner in Norfolk, gathered some 16,000 rebels on Mousehold Heath north-east of Norwich beneath “an aged oak, with wide-spreading branches” (Russell 1859) which they named the Oak of Reformation to foment rebellion and tear down boundaries put up during enclosure. Like the Martyr’s Tree Kett’s Oak, as it has come to be known, still stands, and is listed alongside the Martyr’s Tree amongst the 50 Great British Trees. These trees now not only represent the historical heritage of the British landscape, but also the folklore of resistance that they symbolise.

The ritualised oath-swearing which took place in Tolpuddle, and indeed in the wider early trade union movement, has its roots of esotericism in the rituals of Freemasonry (Firth & Hopkinson, 1974). Trade unionists all over Britain would use a similar ritual to bind workers in solidarity, but also “to prevent a leakage of plans [and] to intimidate potential defaulters” (Oliver, 1966). The testimonies of Legg and Lock gave witness to the ceremony involved in the oath-swearing. Lock told how he and four other men including Legg went to Standfield’s house whereupon they were blindfolded, knelt down and were read Bible passages. They were asked to kiss a book while blindfolded. The blindfolds were taken off and they were shown paintings of Death and a skeleton, and James Loveless, the son of George, spoke the words ‘Remember your end’ as the painting of Death was shown, reminding all gathered of their mortality. (Morning Chronicle, 1834)

Though rooted in Christianity through use of the Bible, the ritual actions speak to a form of magic binding, a “mystic bond” (Oliver, 1966) as worded in a document sent from Yorkshire down to Dorset detailing the methods and reasoning for trade union oath ceremonies, which found its way into the possession of George Loveless. Loveless described himself as “from principle a Dissenter, and by some in Tolpuddle it is considered as the sin of witchcraft” (2005). The secrecy of Friendly Societies as well as the stigma attached to the risk of their establishment is certainly reminiscent of legends about Witches’ Sabbaths and occult procedure. The passing of ceremonial procedure amongst working class communities all over the country also speaks to a transmission of folk knowledge in the fringes of society.

Here the ground has been laid for legends. In the following posts, we shall look at how commemoration of the Martyrs in Tolpuddle has expanded into ritual festivity, ongoing preservation and onomastics in the following centuries.

Bibliography

Empson, M. (2018). 'Kill all the Gentlemen' Class struggle and change in the English countryside. s.l.:Bookmarks.

Firth, M. M. & Hopkinson, A. W. (1974). The Tolpuddle Martyrs. 2nd ed. Wakefield: EP Publishing

Loveless, G. (2005). Victims of Whiggery. s.l.:TUC Tolpuddle Martyrs’ Memorial Trust

Norman, A. (2008). The Story of George Loveless and the Tolpuddle Martyrs. s.l.:Halsgrove.

Oliver, W. H. (1966). Tolpuddle Martyrs and Trade Union Oaths. Labour History, Volume 10, pp. 5-12.

Russell, F. W. (1859). Kett's rebellion in Norfolk : being a history of the great civil commotion that occurred at the time of the reformation, in the reign of Edward VI. London: Longmans.

This Is The Tree That A Village Fights For (1969) Western Daily Press, 14 April. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0004973/19690414/002/0002?browse=False [Accessed 26 November 2024]

Western Circuit - Dorchester, Monday. Crown Court. Trades Unions. (1834) Morning Chronicle, 20 March. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000082/18340320/009/0004?browse=False [Accessed 26 November 2024]

Ritualised Remembrance and Commemorative Landscape

The centenary of the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ sentencing and deportation would see the most significant revisioning of the landscape of the village and its green in remembrance of the six men. But even in prior years, ritualistic remembrance began taking place that would build towards the Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival now held in mid-July every year. By 1875 enough time had passed to view the era of the Martyrs as consigned to history. In March 1875 in nearby Briantspuddle the Dorset Branch of the Agricultural Labourers’ Union arranged the first organised commemoration of the Martyrs, and honoured the sole Martyr who had returned permanently to Tolpuddle - James Hammett. The Western Daily Press described it as “a remarkable celebration” (1875) where Hammett was gifted an engraved silver watch and he spoke publicly for the first time about his ordeal.

In 1912, two years after Hammett’s death, a memorial arch was unveiled on Whit-Monday outside the Methodist chapel built on the site of the barn where George Loveless had preached (Firth & Hopkinson, 1974). After his death Hammett was buried in the churchyard of St John the Evangelist, and a new headstone was commissioned in 1933 to be placed there during the centenary.

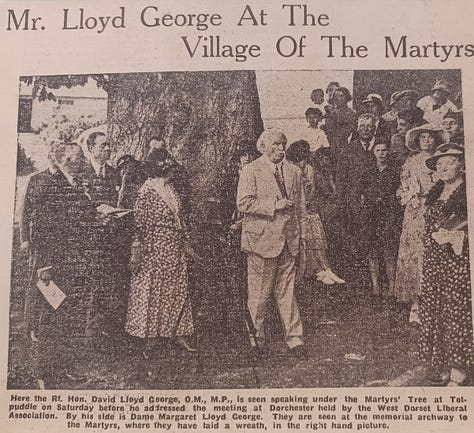

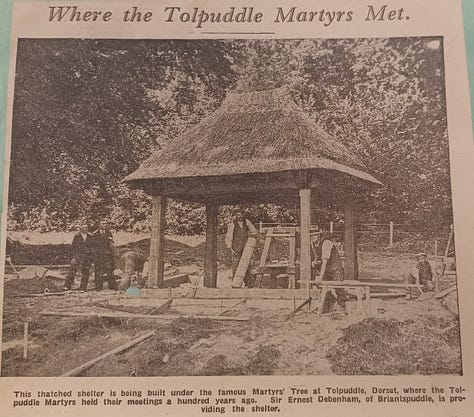

The official centenary event in 1934 took place over the August Bank Holiday weekend, and included the unveiling of six memorial cottages to house retired agricultural workers, and also serve as “a permanent symbol of tribute which the trade union movement was paying to the six brave men who lived in that village.” (Warwick and Warwickshire Advertiser, 1934). The former Prime Minister David Lloyd George attended and gave a speech under the Martyrs Tree, re-energising its symbolic association with the Martyrs, and a thatched memorial shelter was erected on the green next to the tree.

Perhaps the most fascinating example of ritual commemoration around the centenary came on 28th February 1935. TUC council member John Marchbank, having visited Canada to sprinkle soil from Hammett’s grave onto that of George Loveless, came to a ceremony in Tolpuddle to sprinkle soil from Loveless’s Canadian grave onto Hammett’s. William Kean, then President of TUC, stated of the occasion “This soil is sacred to trade unionists, as this is a sacred place.” (Daily Herald, 1935) showing how the mythos of the village there had led to a political sanctification of the men, and the material of their graves elevated to a form of relic status.

These actions demonstrate temporal augmentation of the landscape, where “the physical commemorative landscape of Tolpuddle is neither settled nor timeless…the otherwise ephemeral spectacle created by outsiders on one day a year is embedded in the locality” (Kean, 2011). The village’s once and future connection with nascent trade unionism means its geographical features are constantly being reviewed or renewed within its association as time passes.

Here we have examined the establishment of new symbols in the Tolpuddle landscape as well as ritualised remembrance beginning to take place. Next we will look at the ways in which the symbolic memory is preserved through activism, pilgrimage and onomastics.

Bibliography

Firth, M. M. & Hopkinson, A. W. (1974). The Tolpuddle Martyrs. 2nd ed. Wakefield: EP Publishing

Kean, H. (2011). Tolpuddle, Burston and Levellers: the making of radical and national heritages at English labour movement festivals. In: L. Smith, P. Shackel & G. Campbell, eds. Heritage, Labour and the Working Classes. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, pp. 266 - 282.

The Tolpuddle Martyrs. Memorial Cottages Dedicated by T.U.C. Chairman (1934) Warwick and Warwickshire Advertiser, 8 September. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0001670/19340908/056/0003?browse=False [Accessed 3 December 2024]

Trades Unionism Forty Years Ago (1875) Western Daily Press, 26 March. Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0000264/18750326/038/0004?browse=False [Accessed 2 December 2024]

Tribute To Martyred Villagers - Canadian Soil Placed on Tolpuddle Grave (1935) Daily Herald,1 March. Available at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000681/19350301/233/0013 [Accessed 3 December 2024]

Preservation, Pilgrimage and Onomastic Commemoration

Beyond the centenary, and with the ever-changing political landscape of the UK, sentiments towards Tolpuddle moved towards preservation later in the 20th century. This was felt especially with the Martyrs Tree as it continued to grow and was acquired by the National Trust in 1934 along with the rest of the green. It has been shown in the previous two posts how the Martyrs’ Tree gained folkloric status and became involved in ritual remembrance of the Martyrs. It has held such historic significance and affection by the villagers that, emboldened by the legacy of their forebears, in 1969 they rose up in protest after the parish clerk agreed to the Trust felling the tree when its trunk began to split.

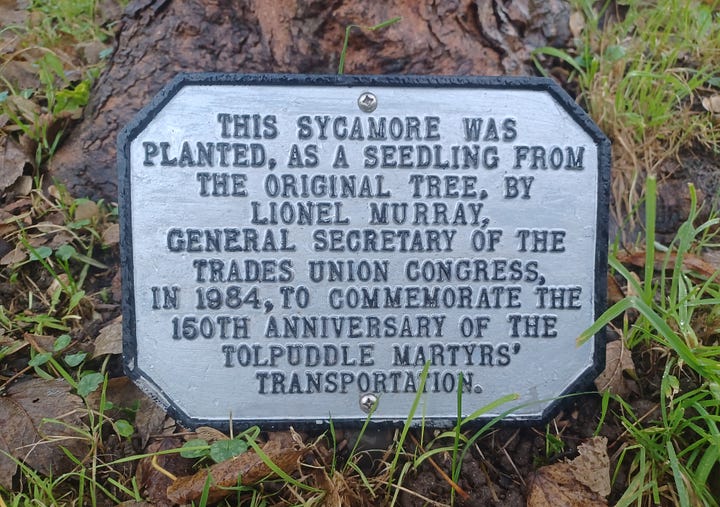

The campaign proved successful, and a band was administered to its trunk which still holds to the present day. In light of the tree’s uncertain future as it ages, the Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival that took place on the 150th anniversary in 1984 was commemorated with a seedling from the Martyrs’ Tree being planted, so as to continue its legacy when the original eventually dies.

The village’s ongoing association with the Martyrs has also inspired the naming and renaming of local sites and businesses, including the local pub. Formerly the Crown Inn, General Secretary of the TUC Vic Feather hosted the official unveiling of the pub’s sign with its new name the Martyrs Inn, as suggested by Hall and Woodhouse Brewery in 1971. (Western Daily Press, 1971) The cottage where the Martyrs met to swear their oaths is now two houses numbered 55 and 57 Martyrs Cottage.

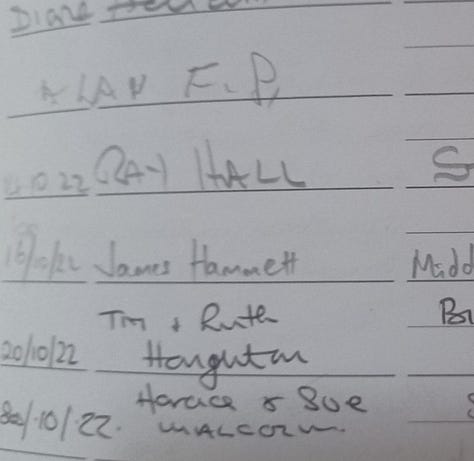

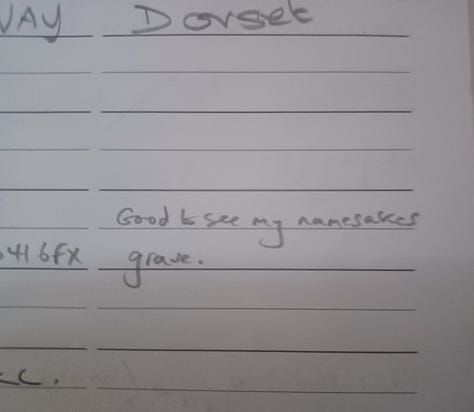

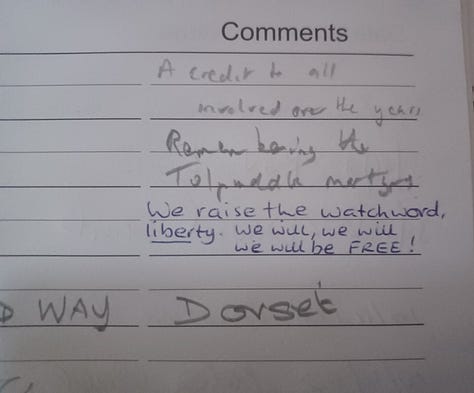

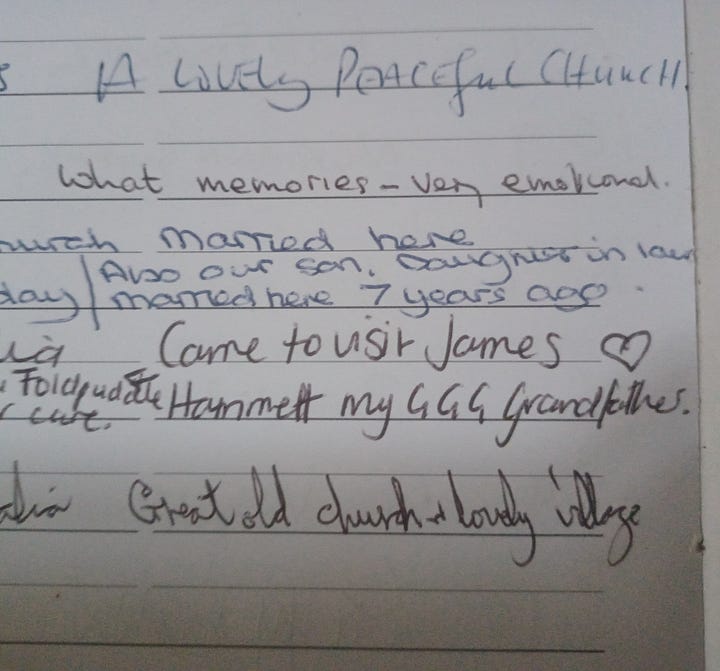

The village and its Martyr-associated sites have also become a place for pilgrimage, both during the annual Festival and throughout the year. James Hammett’s grave has an annual wreath-laying service during the Festival, and when I visited I was surprised to find visitation stones laid on his headstone as is traditional in the Jewish faith. This was an interesting example of a tradition expanding beyond its religious and cultural origin. While visiting the church I noted that their visitors’ book had several messages from the Martyrs’ descendants, as well as from tourists and political pilgrims.

Pilgrimages by political groups have also taken place historically and in the modern era. During the centenary celebrations, the commemorations began at Dorchester before the congregated trade unionists walked the seven mile journey to Tolpuddle for the unveiling of the memorial cottages and Hammett’s headstone (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1934). Seventy six years later, around 60 people marched from Dorchester Prison to the Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival in protest of a law banning prison officers from taking industrial action (BBC News, 2010), a powerful tribute to the men who paved the way for their right to do so.

The history of Tolpuddle and its Martyrs is rich with legend, ceremony and ritual. The narrative of their ordeal gained traction over time, and a symbiosis between the landscape of the village and its political memory is constantly evolving. Acts of commemoration and ritual have continuously emerged, even as the nation’s interest in trade unionism and labour politics has waxed and waned over time. With the bicentennial only a decade away it will be interesting to note what further memorialisation will be enacted on this small but significant site.

Bibliography

This Is The Tree That A Village Fights For (1969) Western Daily Press, 14 April. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/BL/0004973/19690414/002/0002?browse=False [Accessed 26 November 2024]

Mr Feather, making a martyr of the village pub (1971) Western Daily Press, 17 August. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0004973/19710817/004/0004 [Accessed 3 December 2024]

The Tolpuddle Martyrs. First Trade Unionists’ Fate Related At Bath (1934) Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 3 March. Accessed at: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000514/19340303/189/0022 [Accessed 3 December 2024]

Prison officers march to Tolpuddle over union rights (2010) BBC News, 18 July. Accessed at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-dorset-10672629 [Accessed 10 November 2024]